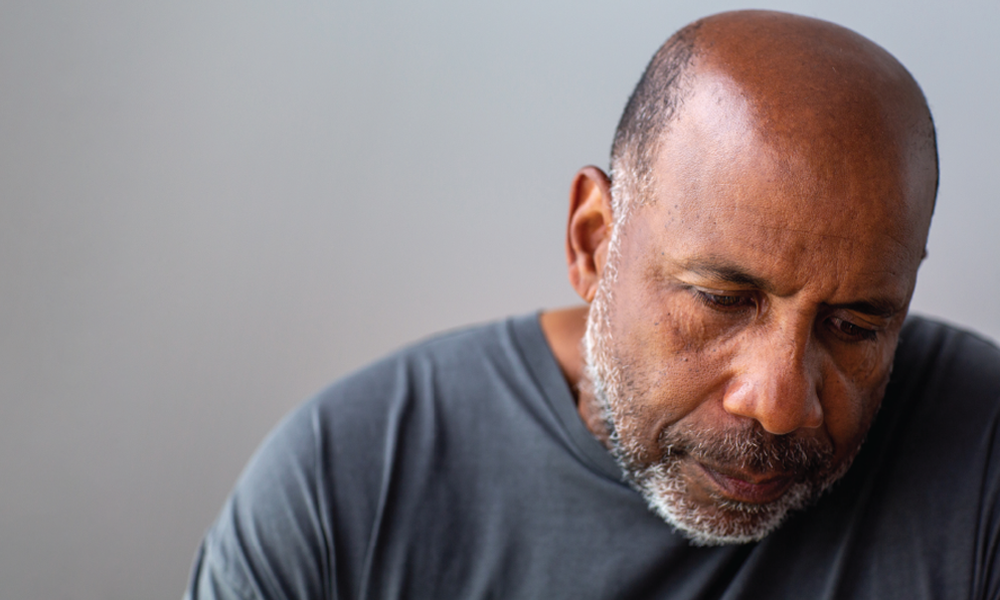

Why do I still feel badly about my sins after I’ve confessed?

I’ve been to confession, and I know that God has forgiven my sins. But I still feel badly about them. What should I do?

I’ve been to confession, and I know that God has forgiven my sins. But I still feel badly about them. What should I do?

Thank you so much for reaching out and for asking this question. In fact, while we know that Jesus forgives our sins in the sacrament of reconciliation, I will often talk with people who experience what you described. There are times when we just can’t seem to let our sins go.

In order to begin to address what is happening in these moments, I think it is important to note what we are really talking about when we discuss God’s mercy extended to us in the sacrament of confession.

We know that God does not brush aside our sins or dismiss them when he forgives. Quite the opposite. God takes sin incredibly seriously. God takes sin so seriously that he made forgiveness possible by taking on human nature, living on this earth, suffering in his body, dying, descending into the abode of the dead, and rising from the dead in order to be able to forgive our sins. All of this was the cost of being able to forgive us.

Remember, God is merciful. But God is also just. And justice demands that the consequences of sin are carried out. Jesus took the weight of the sins of the world upon himself at the crucifixion and allowed the evil that you and I have chosen to overwhelm him to the point of death.

This is one of the reasons a piece of art (or a movie) depicting the Passion of Jesus is both helpful and inadequate. They are helpful because they remind us that my sin cost Jesus his very life. They are inadequate because they can only convey a certain amount of suffering. We can only see the surface wounds (like the horrible wounds of the scourging at the pillar); we can’t see what it cost Jesus internally to bear the suffering that should have come to me.

Scripture states, “The wages of sin is death.” This means that the consequence of sin is death; death is the result of sin, the price of sin. Jesus paid that price. In a free decision of pure love for us, he embraced the cross so that you and I could know freedom, life and mercy.

Furthermore, Jesus made it possible for us to experience this freedom, life and mercy when he breathed on his Apostles and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit … those whose sins you forgive are forgiven. Those whose sins you hold bound are held bound.” Jesus gave the Apostles (and their successors, the bishops and priests) the power to forgive sins because God wanted us to know this mercy for ourselves. He gave this incredible sacrament so that you would know that his sacrifice was not merely for “the world” but was for you.

Now, with that being established, why would we go to confession and still feel badly? I think that there are at least three sources of these feelings.

The first is when we become aware that our sins have consequences in other people’s lives. Our choice has impacted another person in a negative way. Because of this, a person could go to confession and truly know that they have been forgiven but feel tortured by the reality that God’s forgiveness does not miraculously undo what that person’s decision caused to happen. Because I gossiped, someone now has a bad reputation, and I can’t undo that. Because I acted out in anger, another person is now physically or emotionally wounded. Because I stole, someone now has less. Of course, the list of the consequences of our choices could go on forever. But the fact remains that my decisions may have injured someone else’s life. It is possible that our decisions have ended someone else’s life.

What does a person do then? Yes, God has forgiven them. But there are consequences that someone else is enduring. This is one of the places where the Church’s teaching on restitution could come into play. The Church teaches us that, if I am truly repentant of my sins, I ought to do all I can to make up for my sins according to my ability.

This is not at all believing that we are “earning” forgiveness. Jesus is the only one who can pay the price for my sins. But the doctrine on restitution asserts that we are obliged to do what we can to restore what was taken, lost or damaged. For example, if I were to steal money from my parents, I ought to go to confession to receive the forgiveness of the Lord. But I should also seek to give back what I took. If I have damaged someone’s reputation, I ought to try to heal that damage. If I have lied, I ought to do what I can to clarify the truth.

It might be that you are still feeling badly about your sins because you have not yet sought to restore what your choices damaged. This could be your conscience moving you to the next step.

Now, there are many times when we are not able to restore what was wounded. There are many times when the damage has been done and there is no going back. Consider the case of the person who has ended someone’s life in a drunk driving accident, or someone who has made a series of choices that mean that they can no longer be in contact with their children. In those cases, we do what we can to make it up to the others involved. But then we have to be willing to pray for them and entrust them to God. It might be that all I can do for the rest of my life is offer up penances and sacrifices for their healing. If that is what I can do, then that is what I should do.

The second kind of reason why one might have been forgiven but still feels badly is because of shame. Maybe their sin had come to light and “now someone else knows.” I think that many of us have had this experience. I know that God has extended his mercy to me, but what is really bothering me is that there is someone out there (or a few “someones” out there) who know this about me. There are people who know what I’m capable of. In these cases, we may be very grateful to the God who has met us in our need and forgiven our sins, but every time we think of the fact that “someone else knows,” we have this pain in our gut.

This is good. If this is the case, we can identify the source of our feeling badly. And the source is merely pride. I had wanted people to think that I am better than I actually am. But now they know that I have the capacity to choose evil, and it bothers me. This is a good thing, because pride is the deadliest sin out there. And if I am a slave to pride, no matter how much God offers his mercy to me, I will shrink back from entering into its fullness and joy, because I am more concerned with what other people think of me than I am with God’s love for me. It is definitely not pleasant. In fact, it is horribly painful. But Jesus’ death did not just conquer the guilt of our sins, but also conquered the pride that undergirds all of our sins.

The last reason why a person may still feel badly after having been forgiven is because they are so saddened by the fact that they have grieved the Lord’s heart. We even pray this in the Act of Contrition, “… and I am sorry for my sins, because I dread the loss of heaven and fear the pains of Hell, but most of all because they have offended you, my God, who are all good and deserving of all of my love ….” There are sensitive souls out there whose hearts are broken when they consider the cost of forgiveness.

For them (and for all of us), we need to remember this: Jesus Christ came to save sinners. This was the motive behind his coming to earth. God wants us to experience his love. God wants us to be healed. The reason Christ embraced his cross was so that you and I could be set free. Because of this, we have a certain confidence. We are confident that, when we go to confession, we are making this decision, “God, I will not let what you did on the cross go to waste on me.”

You’ve placed your sins at the foot of the cross in the sacrament of reconciliation. You do not need to pick them up and take them with you when you leave.

Father Michael Schmitz is director of youth and young adult ministry for the Diocese of Duluth and chaplain of the Newman Center at the University of Minnesota Duluth. Ask Father Mike is published by The Northern Cross.